Art is in every book you read. Marcel Duchamp, notorious in the art world forhaving successfully argued that a urinal is art—thus ushering in the Avant Garde—would probably agree with me. Monsieur Duchamp aside, images are both essential and important for all modern-day book covers. They’re the first and most obvious means authors and publishers inject art into books, and since covers are what may initially attract a potential reader, they help sell books.

The body of a book may also include illustrations, not only to engage a reader, but also to enlighten. Remember how your child began to recognize the letter “A” after you’ve shown it to him with images (or “pictures”) of objects beginning with the letter “A”? An apple, for instance. We introduce children to reading with picture books.

Admittedly, my children’s picture book expertise is fairly limited and not up to date (my son is now a grown man), but selecting books for my child awakened me to the artistry in picture books. I learned to identify various kinds of popular children’s books from their styles of illustration—for instance, the Berenstain style associated with the eponymous books of these well-known authors. Then, of course, a mother-in-the-know exposed her child to the books of Maurice Sendak.

Children’s book reviewers love Maurice Sendak for dealing with the “little demons” that plague children as they’re growing up. He illustrated his stories with pictures that, in their vividness (e.g., creatures with horns and long sharp teeth) probably help make those demons more concrete for both parents and children. And making them concrete might help them deal with those demons.

When I read books for myself—excluding those such as art books that must contain pictures to be more fully understood and appreciated—I love looking at illustrations (not background decorations or text embellishments) when I find them in the book content. They help me imagine and understand what I read. I specially love them in fiction. So, before I was intrigued as an adult by children’s picture books, I have always had a certain fascination for illustrated books.

One of my favorite books is an old almost tattered copy of a collection of Jane Austen’s novels. I have kept this book for the drawings of Victorian figures illustrating scenes from the novels. These drawings grace the title page, the top of the first chapter, and the page after the end of the book. Before Masterpiece Theater and my exposure to films of Victorian characters, these drawings shaped my limited conception of everything that was old English.

Now, an illustrated copy of Pride and Prejudice is permanently installed in my kindle. I bought it not for the text, which I’ve read many times, but for the late 19th-century Hugh Thompson illustrations in ink.

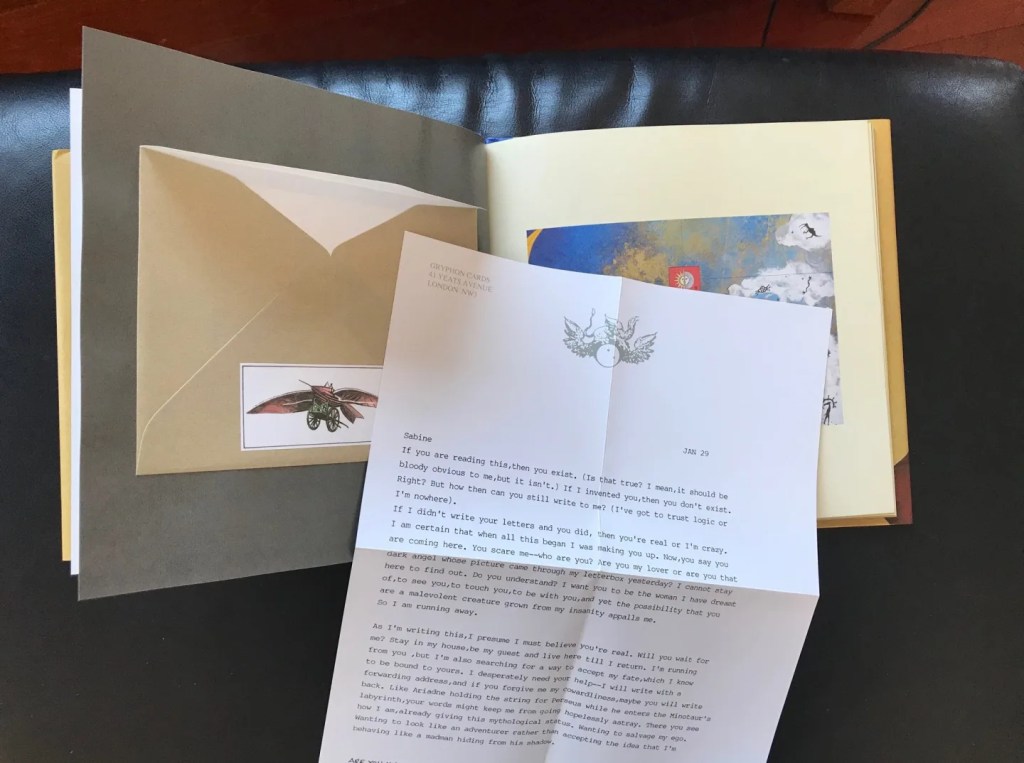

Two other books in my favorites list are also illustrated. Like Sendak in his children’s books, the writers are also the illustrators: Nick Bantock’s Griffin and Sabine Trilogy (see my review) and Antoine de Saint Exupery’s The Little Prince. These two magical books of fiction are about life—seen from the unalloyed wisdom of a child (The Little Prince) and the introspective musings of artists (Griffin and Sabine Trilogy). The books themselves constitute the art instead of art as a theme or a thread in the stories. I recommend them highly to all adult readers.

Today, we take picture books for granted. We love images. They seem to be such a natural part of modern life. We whip out our cell phones and take them of ourselves, of events, of sceneries, and everything that catches our eye or helps us preserve the memory or record of an instant in time.

As hooked as we are by images, have you ever wondered about the origins of picture books?

They have a rather illustrious past dating back to maybe the fifth or sixth century that subsequently blossomed during the ninth-century reign of famous conqueror Charlemagne. He spawned a period of artistic and cultural ferment that historians have labeled the Carolingian (from the Latin “carolus magnus”) Renaissance.

Picture-book making flourished under Charlemagne along with the construction of classical buildings that have unfortunately not withstood the assault of man and time. Thus, the most enduing part of his legacy resides in pictures books. As if the term ”Carolingian Renaissance” is not intimidating enough, historians have also saddled those old picture books with an equally daunting, but apt, label: manuscript illuminations or illuminated manuscripts.

Produced before the advent of the printing press, these manuscripts were handwritten on parchment and illustrations were painted in tempera and gilded with gold or silver ink. And in the earlier years, the scribes were quite often also the illustrators (like Mr.Bantock and Comte Saint Exupéry).

Historians believe Charlemagne encouraged (commanded maybe?) the production of those medieval manuscripts to teach a largely illiterate populace about religion—many manuscripts were psalters or prayer books (aka book of hours). They think Charlemagne himself didn’t know how to read, and it’s tempting to imagine that this fact may have sparked, at least in part, his directing scribes in monastic scriptoria to create illuminated manuscripts.

Because bookmaking started as a thriving art genre in medieval times, I would argue that art is in every book’s genes. Now that most people can read, pictures are no longer necessary in most books. And yet, our fascination with images in fiction live on maybe stronger than ever, incarnated as graphic novels or comic books. The latest illustrated version of Pride and Prejudice is an adaptation of the story into o a digital graphic novel.

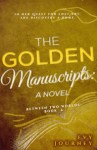

My latest novel, The Golden Manuscripts: A Novel, the sixth and final book of the series, Between Two Worlds is about a quest for illuminated manuscripts stolen during World War II, a tale inspired by the actual theft of medieval illuminated manuscripts by an American soldier.